Height is the canonical quantitative trait in humans. It’s easy to measure and has a high heritability (around 0.8 - see references in Visscher et al 20081). Interestingly, it varies significantly across populations, even on a sub-continental level. Recently, there have been a number of interesting papers about this observation and the extent to which it’s driven by selection. Briefly:

- Height varies across Europe roughly, though not exactly, in a North-South gradient.

- Some of this variation in height is genetic.

- Some of the genetic variation in height is driven by selection.

Based on my own work, I think that there are at least two independent episodes of selection in European history, and present-day height variation largely corresponds to variation in ancestry.

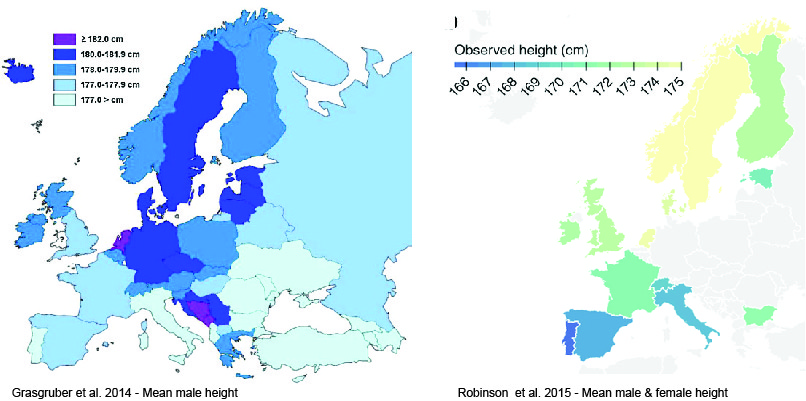

###The distribution of height Ignoring the subtleties of measurement, average male height in present-day Europe is around 178cm (5’10”) with a standard deviation2 of 7cm, while average female height is around 15cm lower. Between-country differences in average height are up to 15cm, or around 2sd (Wikipedia, Grasgruber et al. 2014). You can see that there’s a rough North-South gradient, with Northern Europeans generally taller than Southern Europeans, but it’s not perfect.

###Genetic basis for variation in height At least some of this between-population variation in height has a genetic basis, though it’s not clear exactly how much. For example, looking at GWAS hits, height-increasing alleles are more common in Northern Europe, and height-decreasing alleles more common in Southern Europe (Turchin et al 2012). Another argument for a strong genetic effect is that despite an overall increase in absolute height over the past 100 years, the relative heights of European countries have remained relatively constant (Graham Coop). Robinson et al. (2015) get at this question by estimating that 9-41% of the variance in predicted genetic height can be accounted for by between-population factors, but it’s not clear to me how this would translate to a proportion of the total genetic effect. Ultimately I feel like estimating this number exactly would be murky and not particularly interesting.

###Selection on height

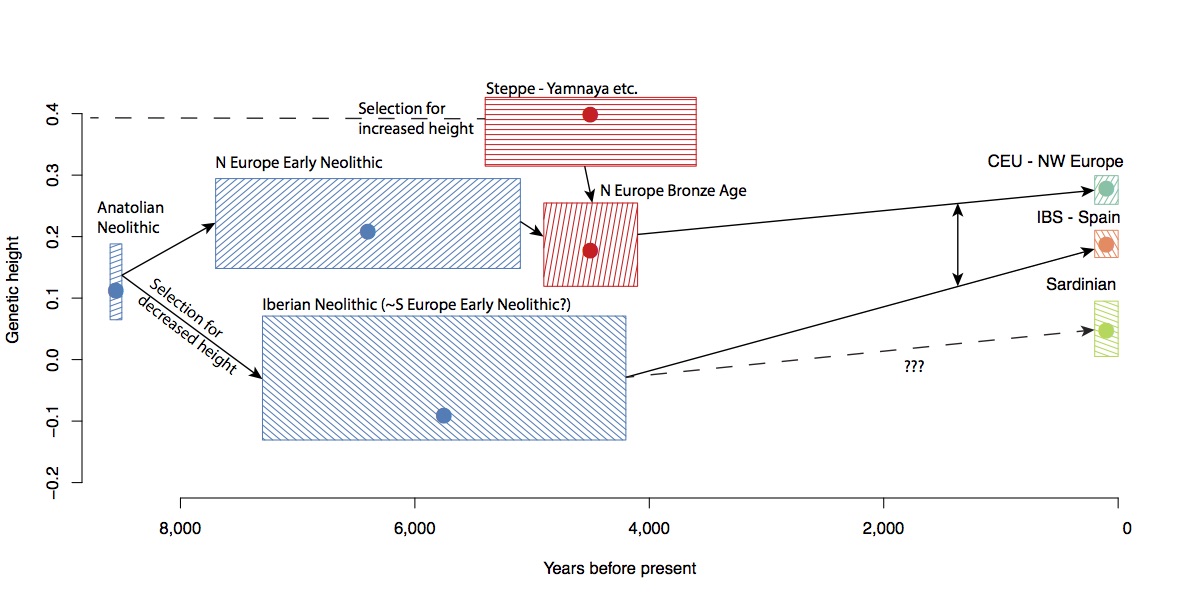

Turchin et al. (2012) showed that the extent of differentiation of height-affecting alleles is greater than can reasonably be explained by neutral processes, an observation confirmed by Berg & Coop (2014) and Robinson et al (2015). Systematic investigation is limited by sampling, but one interesting observation is that this effect seems to be particularly strong in Sardinia (Zoledziewska et al. 2015). In Mathieson et al. (2015), we tried to look at the changes in genetic height over time using ancient samples and found evidence for two independent signs for selection - one for decreased height in Neolithic Iberia, and one for increased height in Bronze Age Steppe populations.

This is a modified version of a figure from our paper, showing estimated genetic height in various ancient populations with arrows representing major population relationships. It’s clear that Neolithic Iberians had substantially lower genetic height than Northern Europeans (mostly from present-day Germany in this case). I assume, though this needs to be tested, that this represents a generally southern European, rather than specifically Iberian, effect. So my current model is one where the present-day variation in height is driven by variation in the proportions of both Steppe and Southern European Neolithic ancestry. Of course, this model doesn’t exclude additional or ongoing selection, or extra sources of ancestry.

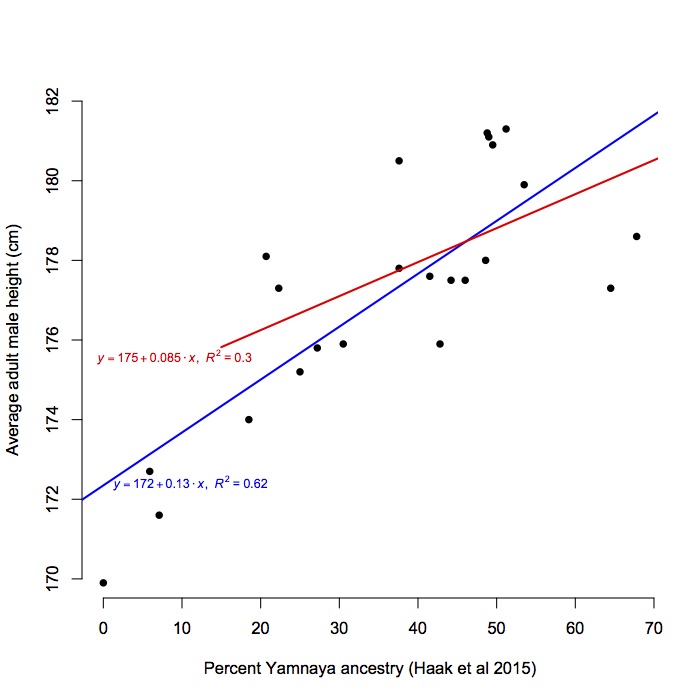

Sardinians provide at least one datapoint consistent with this model because (unlike IBS, say) they have little or no Steppe ancestry, and their genetic height, like their genome-wide ancestry, is consistent with being derived almost entirely from a Southern Early Neolithic (i.e. farmer) population. This is genetic height, which won’t necessarily behave like actual height, but one general prediction of this model is that average height across European countries should increase as the proportion of Yamnaya ancestry increases, which seems to be the case (height data mostly from Grasgruber et al. 2014 and Arcaleni et al. 2006; data; code).

A linear model fits with R2=0.6 and implies that each percent of Yamnaya ancestry adds 1.3mm of height (p=9e-6). The three points in the bottom left are Sardinia, Sicily and Malta3, which are probably not independent, but even removing these points we get a positive trend R2=0.3, p=0.01. Yamnaya ancestry is highly (0.9) correlated with latitude, but a linear model of Height~Latitude fits worse than Height~Yamnaya (R2=0.49 vs 0.6). I think at present we can’t reliably tell the difference between Northern and Southern Early farmer ancestry but there’s a similar prediction that populations with more Northern Farmer ancestry would be talled.

It would be interesting to look at the heights of ancient populations in this context, although estimating heights from skeletal remains probably makes it a bit noisier. Anecdotally though, I’ve heard that the Yamnaya are talled than other Bronze age populations.

###Discussion All this is fairly preliminary, and there are still a number of problems and open questions. For example:

- The ancient samples are small, and really too sparse to be comprehensive. At the moment, the more sophisticated predictors that use LD information can’t be used on ancient samples, so the genetic height estimates are not as good as they could be.

- We don’t really know which traits are actually being selected, and why. Presumably it’s not direct selection on height, but on some package of correlated phenotypes.

- We don’t know that the relationship between genetic and actual height is stable. For example, one hypothesis is that the Iberian Neolithic populations weren’t actually shorter - their environment promoted greater height, so that they were selected to reduce their genetic height so that actual height would remain at some optimum level. Then these differences in genetic height became exposed recently once environments became more equal across populations.

More generally, it seems strange that height is the only trait for which a robust signal of polygenic selection has been observed. It’s hard to imagine that traits like diabetes risk and lipid levels were not also under selection in this period. I think it’s mostly down to lack of power in the predictors for other traits. Possibly larger GWAS and better predictors will reveal more. Finally, most of the work in this area has focussed on Europe, since that’s where the large cohorts are. But similar dynamics must also have happened in the rest of the world and it’s only by looking at other populations that we’ll be able to understand more generally the process of human adaptation.

###References

Arcaleni Secular trend and regional differences in the stature of Italians, 1854–1980 2006

Berg & Coop A Population Genetic Signal of Polygenic Adaptation 2014

Galton Regression toward mediocrity in hereditary stature 1886

Grasgruber et al. The role of nutrition and genetics as key determinants of the positive height trend 2014

Robinson et al Population genetic differentiation of height and body mass index across Europe 2015

Mathieson et al. Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe 2015

Turchin et al. Evidence of widespread selection on standing variation in Europe at height-associated SNPs 2012

Visscher et al. Heritability in the genomics era — concepts and misconceptions 2008

Zoledziewska et al. Height-reducing variants and selection for short stature in Sardinia 2015

###Notes

-

Actually, this number hasn’t changed that much since Galton first estimated it to be about 2/3 in 1886, inventing regression in the process. ↩

-

The tallest man in the EU is 7.7 standard deviations taller than the mean! ↩

-

I can’t find a good reference for Maltese height, so this number is taken from Wikipedia. ↩