Lactase persistence (LP) in Europeans (caused by the SNP rs49882351) is probably the strongest known signal of selection in the entire human genome, and one of the few that looks like a classic hard selective sweep. However, there’s still quite a lot of uncertainty about the origin of this mutation, and the strength and timing of selection. Recently ancient DNA from Europe has started to fill in the answers to some of these questions, which I discuss here.

###Modern distribution of lactase persistence. In Europe, the derived allele of rs4988235 ranges in frequency from something like 10-80%. (for example, 9% in 1000 Genomes TSI up to 74% in CEU). It seems to be generally more common in Scandinavia, the British Isles, the Low Countries, Northern Iberia, and Eastern Europe and actually quite low frequency outside these regions.

Outside Europe, lactase persistence is common in parts of Africa, particularly West Africa, the Middle East, and India. Most of these have independent origins, but remarkably, the lactase persistence allele in India is the same as the European allele (Gallego-Romero et al. 2012).

The selection coefficient on the allele is typically estimated from haplotype structure to be on the order of 0.07-0.1 (Bersaglieri et al. (2004), Tishkoff et al. (2007), Itan et al. (2009)) in northern European populations, although some estimates are much lower (Peter et al. (2012) estimated s=0.025). All these estimates have large confidence intervals. These high numbers seem implausibly large to me. The age of the allele can be estimated from modern data, but the confidence intervals are generally too large to be useful although they largely support a recent origin, say in the last 10,000 years. Putting this together, Itan et al. (2009) argue that the allele originated somewhere in central Europe, and was first strongly selected 7,500 years ago, before being dispersed around Europe by the early farming culture known as the LBK.

Despite these large estimated selection coefficients, it’s not really clear why it would be so strongly selected. Maybe just the extra calories that you can get from milk were beneficial. Perhaps it helped to avoid calcium deficiency or some other form of malnutrition

###Ancient DNA results Burger et al. (2007) were the first to report a low frequency of LP in the early Neolithic, albeit with a small sample. In Mathieson et al., we found that the earliest evidence for the LP allele was in a Bell Beaker sample dates to around 2300 BCE. We didn’t find any evidence for LP in early farming populations like the LBK, or in early Bronze age steppe populations like the Yamnaya. In as-yet unreported data, we find a few copies of the allele in the Srubnaya - a later steppe population who seem to have some European Farmer-like ancestry. Using these data as a time series, we estimated that the selection coefficient is around 0.015 - much lower than any haplotype based estimate.

Allentoft et al. reported a sample that was geographically similar, but later in time. They found LP in the Bronze Age, both in Mainland Europe, and in the Steppe. Their steppe samples with the allele are relatively early, and they suggest that the allele may have originated on the steppe and have been brought to Europe by the late Neolithic migrations from the steppe to Europe. One potential problem with this argument is that their inference of the allele in the early Bronze Age steppe is based on imputation from a modern reference panel into the ancient samples, which might lead to imputing the allele incorrectly. See the next section for more discussion of this.

There are earlier reports of the LP allele in the Iberian Neolithic (Plantinga et al., 2012) and even earlier Middle Neolithic Sweden (Malmström et al., 2010). I’m mildly skeptical of these results because 1) They only estimate contamination from mtDNA, rather than the autosomes 2) rs4988235 is a C->T SNP where T is the derived allele, so aDNA damage could be an issue.

###Imputation

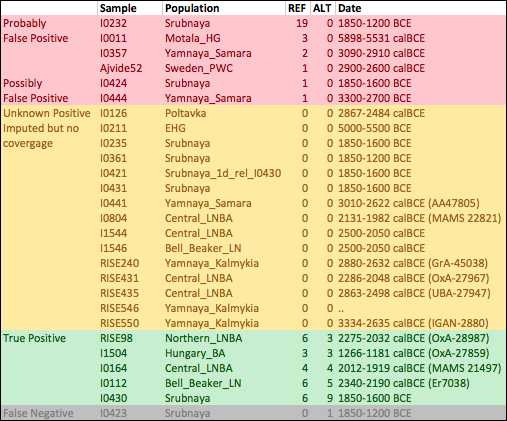

This might be a problem if the haplotype on which the SNP arose is present in the ancient samples. Since this haplotype would be identical apart from a single SNP to the one which is selected, and the latter is much more common in modern populations, it’s possible that you would impute the derived allele incorrectly. To test this, I removed rs4988235 from an extended version of the Mathieson et al. dataset, computed genotype likelihoods for the ancient samples, tried to impute it back using Beagle and the 1000 Genomes phase three reference panel. Here’s a table with the samples that are confidently imputed to have the allele, with the number of REF and ALT reads that actually hit the SNP. You can see the actual haplotypes here, in the same order as the table.

In 5 out of 6 samples where I know the derived allele of rs4988235 is present, it is imputed correctly. It’s also imputed to be present in 21 other samples. Of these 21, 6 have at least one read covering the SNP, and none of them show the ALT (derived) allele. Most of these only have one read, but one of them has 19 REF reads, so it surely doesn’t have the allele. Probably at least two or three of the others are false positives too2. So the imputation definitely has both false positives and false negatives, though it’s hard to estimate the rates from this analysis. I think we can’t yet confidently say from imputed data whether or not the allele was present in early Bronze Age steppe populations like the Yamnaya.

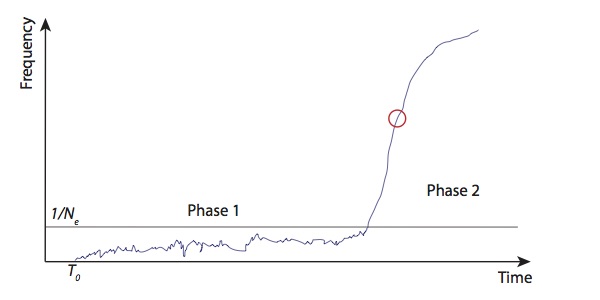

###Selection coefficients One thing that’s quite puzzling about this allele is that looking at the haplotype structure seems to give you much stronger selection coefficients than looking at the direct frequency estimates from ancient DNA. However, I think there’s a simple explanation. Generally, you can split the life of a selected allele into two parts. First (phase 1), when it’s at low frequency, there is a lot of stochasticity in its trajectory, and, indeed, with probability of roughly \(1-2s\), it will disappear. However once it reaches a frequency of roughly \(\frac{1}{N_e}\), its trajectory will be almost deterministic and it will go to fixation relatively quickly (phase 2).

Now, consider two classes of methods of estimating selection coefficients. First, looking at haplotype structure. This is going to tell you the average strength of selection over the life of the allele. The allele appears, you start with one haplotype, and then measure how much it’s been broken up by recombination up to the present. This breaking up of haplotypes happens at a constant rate over time, so if the allele spends a lot of time in phase 1, then this will dominate the estimate. On the other hand, you can estimate the selection coefficient from the allele frequency trajectory. In this case, it turns out that actually you don’t care about phase 1, and all you care about is phase 2. This is because if you know the trajectory then the MLE of the selection coefficient is something like \(\frac{1}{\int_{t=0}^{\infty}f_t(1-f_t)dt}\), so the time when \(f\) is small, i.e. phase 1, doesn’t affect the estimate. In fact, since you only care about phase 2, which is almost deterministic, you can get a pretty good estimate of the selection coefficient just by looking at the rate of increase of the frequency at some point in this phase (say, \(f=0.5\)).

If the selection coefficient was constant over the life of the allele then these two approaches should give the same answer. Since they seem to disagree, I think this is evidence that it was not. Specifically, I think this means that, at some point during the early life of the allele, it was selected extremely strongly, at least in some locality, but that in the Bronze age and later, where we start to see it appear in the ancient DNA data, selection was much weaker. It still reached high frequency, at least in some populations, because by that point it was in phase 2, but certainly wasn’t always as strongly selected as the haplotype estimates would suggest.

###Summary

Here’s my best guess as to the history of this allele: It appeared some time before 2500 BCE, either on the Steppe (if you believe the imputation results), or in Central Europe (if you don’t), or perhaps in some other part of Europe (if you believe the all the ancient DNA results). Then, for some reason, it’s very strongly selected, perhaps \(s\approx0.1\), maybe only locally, maybe only for a short period of time but enough to drive it to a frequency greater than 0.1%. Selection relaxes in the Bronze age but it still drives to high frequency, at least in Northern Europe. It may even have stopped being selected at all. This is actually rather consistent with the Itan et al. result, and it seems plausible to me that the allele first appeared in Central Europe, was spread around Europe by the LBK, before being introduced to the steppe later by migration from Europe.

###References

Bersaglieri et al. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene 2004

Burger et al. Absence of the lactase-persistence-associated allele in early Neolithic Europeans 2007

Itan et al. The Origins of Lactase Persistence in Europe 2009

Malmström et al. High frequency of lactose intolerance in a prehistoric hunter-gatherer population in northern Europe 2010

Mathieson et al. Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe 2015

Mathieson & McVean Estimating selection coefficients in spatially structured populations from time series data of allele frequencies 2013

Peter et al. Distinguishing between Selective Sweeps from Standing Variation and from a De Novo Mutation 2012

Plantinga et al. Low prevalence of lactase persistence in Neolithic South-West Europe 2012

Tishkoff et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe 2007

###Notes