The FADS (fatty acid desaturase) genes encode enzymes which are required for the synthesis of long-chain unsaturated fatty acids from plant-based foods. These fatty acids, which are important for brain development can alternatively be directly obtained from meat and fish. FADS1 and FADS2, which are next to each other on chromosome 11 have been identified as being, or having been, under selection, apparently independently, in many different populations. In Mathieson et al. (2015), the FADS1/2 locus was one of our top hits for selection in Neolithic Europe. The 1000 Genomes Consortium (2015) found that they were under selection in East Asians, and Fumagalli et al. (2015) showed selection in the Greenland Inuit. Before that, Ameur et al. (2012) found evidence for an ancient selective sweep in Africa. It seems likely that these genes are very important for human adaptation to different diets, and that they have an interesting evolutionary history.

The evolution of FADS1 and FADS2

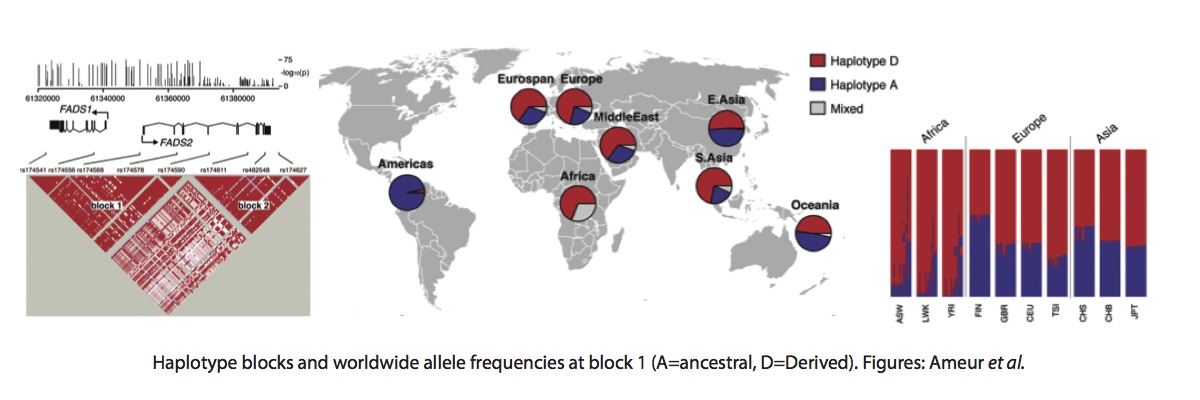

Ameur et al. found that there were two independent LD blocks covering the two genes (See below). Block 1 covers most of FADS1 and the start of FADS2 and block 2 covers the rest of FADS2.

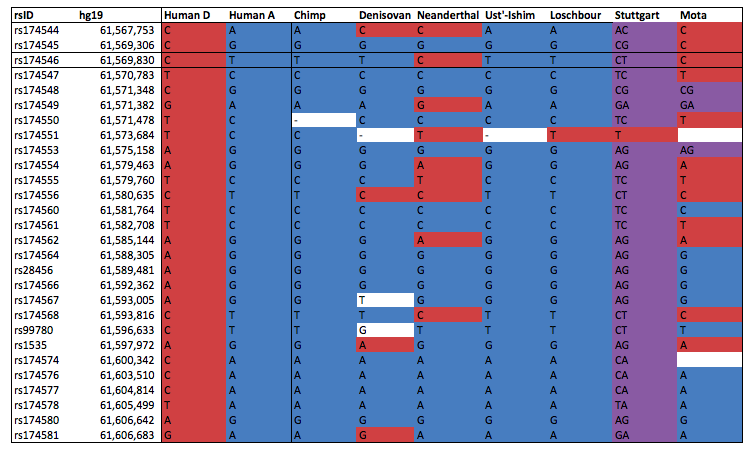

Block 1 contains two major haplotypes - the derived haplotype, which increases the activity of FADS1, is most common in Africa, at intermediate frequencies in Europe and East Asia, and absent in Native Americans. This is and unusual and interesting pattern in itself and given the evidence for a sweep in Africa, Ameur et al. reasonably conclude that this sweep was ongoing at the time of the out-of-Africa event, so the derived allele remained polymorphic in non-Africans and was lost by drift in Americans. However, we now have a lot more ancient genomes available and the story turns out to be more complicated. I looked up the 28 SNPs that Ameur et al. use to define their haplotypes in several high coverage ancient genomes:

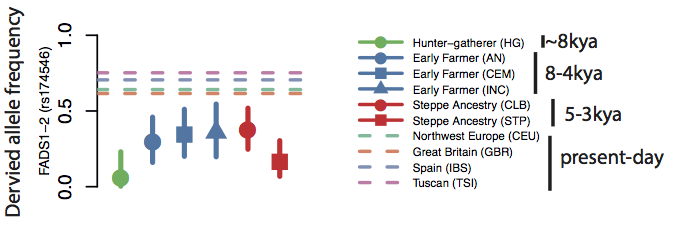

As you can see, it turns out that both the 45,000 year-old Ust’-Ishim individual, and the 8,000 year-old Mesolithic hunter-gatherer from Loschbour are homozygous for the ancestral allele, and that the 7,000 year-old early farmer from Stuttgart is heterozygous. The 4,000 year-old Ethiopian from Mota has the derived allele (if you focus on the first half of the haplotype, which I think is the most important part based on the selection signals). This is rather surprising because it suggests that the appearance of the derived allele in Eurasia might have been very late. Our results from Mathieson et al. seem to confirm this. The top selection signal in this region was at rs174546 and at this SNP, the frequency of the derived allele increases over time from zero in the Mesolithic, through intermediate frequencies in the Neolithic and Bronze age, to around 80% in present-day Europeans:

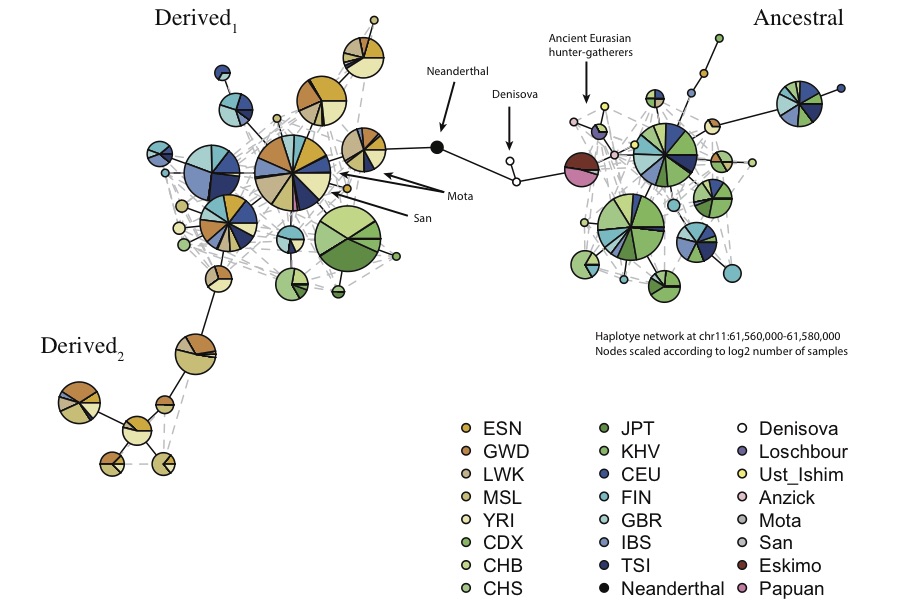

The other extremely surprising thing about this haplotype is that the Neanderthal haplotype is mostly derived! Remember, this haplotype is the one that is almost fixed in Africa. I built a haplotype graph (with pegas) using the 20kb region around rs174546, and data from the 1000 Genomes project, the Simons Genome Diversity Project (SGDP) and some ancient samples, and confirmed that 1) Virtually all present-day Africans (including San and Mbuti), have the derived allele, along with ~80% of Europeans and ~50% of East Asians 2) All ancient Eurasians have the ancestral allele and 3) the Denisovan and Neanderthal haplotypes are intermediate to the ancestral and derived alleles:

Here, African haplotypes are in brown, European haplotypes are in blue and East Asian haplotypes in green. It looks like there are actually two major clusters of derived haplotypes - one which is African-specific and one which is shared with Eurasians. Note that all the inuit (from the SGDP) have the ancestral allele.

Variable selection depending on diet

It’s not obvious what’s going on here. At frist glance, it looks like introgression of the ancestral allele from Denisovans into East Asians, but then it’s hard to explain how Europeans and, especially, ancient Europeans got the ancestral allele at such high frequency. It could be that the derived allele was at intermediate frequency at the time of the out-of-Africa event, and subsequently swept to fixation in Africa (all of Africa?), but not in Eurasia, but then it’s very hard to understand how Neanderthals got the derived allele. It seems like the ancestral allele must have been positively selected at some point, but that’s unexpected because it was clearly disadvantageous both at some point in ancient Africa, and relatively recently in Eurasia.

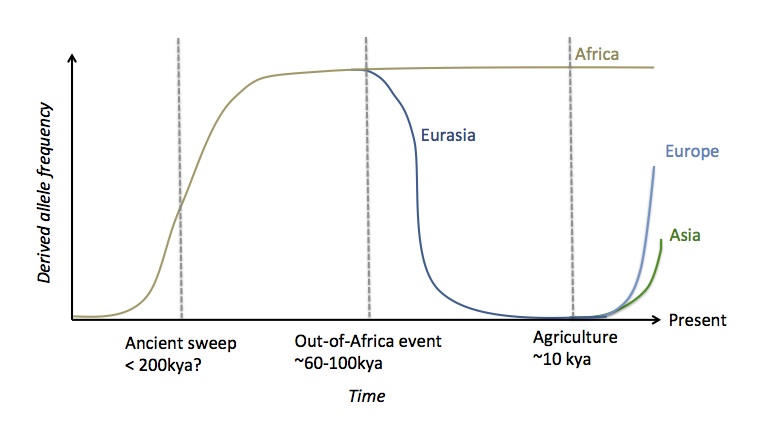

Therefore, I think we have to invoke time-varying selection to explain this pattern. Here’s one explanation:

- The derived allele appears some time around the Neanderthal-human divergence, so Neanderthals, Denisovans, and anatomically modern humans were all polymorphic.

- After the Neanderthal-Human split, the derived allele is selected in humans, because of a change in diet to include more plant based foods. This sweep is complete by the time of the out-of-Africa event (probably much earlier), so the first out-of-Africa modern humans all have the derived allele.

- The ancestral allele then introgressed into early Non-Africans from some archaic population, maybe Neanderthals or maybe some now-extinct modern human lineage, which is still polymorphic. Importantly, this allele is strongly advantageous, because the diet of these early Non-Africans contains much more meat and fish than the diet of their recent African ancestors. The ancestral allele becomes fixed in Eurasia.

- Only after the invention of agriculture, perhaps 10,000 years ago, and a return to a more plant-based diet, does the derived allele become advantageous in Eurasia, and starts to increase in frequency. This late switch explains why the derived allele isn’t present in the Americas, for example.

I don’t know much about paleo-diets, so I don’t know whether it’s true that Upper Paleolithic Eurasian hunter-gatherers ate meat/fish-heavy diets. I have heard it suggested in the context of a source for vitamin D given that, as far as we can tell, these populations do not have the skin-lightening adaptations of present-day Eurasians, and may have had to get much of their vitamin D from environmental sources other than sunlight. This model predicts that we should be able to find some very early Eurasian humans with the derived allele, and also that we should be able to find some Neanderthals (or, just about possibly, Denisovans) who carry the ancestral allele.

Here’s a cartoon of what I think is going on with the derived allele frequency in different populations:

Independent selection at the FADS locus

It looks to me like the Fumagalli et al. haplotype which reduces the action of FADS2 is actually in LD block 2, mostly covering FADS2, and independent of this signal. This is consistent since the Inuit eat a diet that probably contains even more meat and unsaturated fats than any hunter-gatherers, so need to reduce the activity of the FADS genes even more than the ancestral allele at FADS1. This suggests to me that other populations would have fine-tuned the activity of these genes to suit their specific diets, which we should be able to detect, particularly in populations who eat a lot of, or very little, animal fats.

FADS and health

Finally, it’s worth noting that the FADS genes may be important for human health. Rs175546 is one of the strongest GWAS hits for lipid levels, particularly triglycerides (Teslovitch et al. 2010). The derived allele increases total cholesterol and decreases triglyceride levels, and thus may have an effect on coronary artery disease risk, and other health outcomes, though the evidence for this seems mixed. Bear in mind that having been under strong selection does not necessarily imply that the health effects will be large, since the phenotypes that were under selection are probably not the same as the health phenotypes that we’re interested in.

References

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation 2015

Ameur et al. Genetic adaptation of fatty-acid metabolism: a human-specific haplotype increasing the biosynthesis of long-chain omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids 2012

Fumagalli et al Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation 2015

Mathieson et al Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians 2015

Teslovitch et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids 2010.