Why impute?

One of the slightly frustrating things about ADNA data is that it is typically very low coverage. A small number of samples have high endogenous content and complexity, and can therefore be sequenced to high coverage - but this is impractical and/or uneconomical for the vast majority of samples. Even with targeted capture enrichment approaches (e.g. Haak et al.; Fu et al.; Mathieson et al.), coverage is typically on the order of ~1x. It would be possible to generate higher coverage, but it’s unlikely to be practical to generate the sort of coverage (say, ~20x or higher) that would allow you to make reliable diploid calls and generate phased haplotypes.

In terms of analysis, low coverage data isn’t a problem for allele frequency based methods like PCA, \(f\)-statistics, or the frequency-based selection scan we used in Mathieson et al. However we can’t directly use method that need complete genotypes or haplotypes - the majority of population genetic methods - that would, in principle, greatly increase our power for demographic inference (e.g. ChromoPainter etc…) or selection scans (e.g. ihs etc…). There are two ways we could try to get these kind of methods working. First, we could develop these methods so that they can integrate over the uncertainty in the data. Second, we could try and boost the completeness of the data using imputation and/or generate phased haplotypes1, to the point where we can run methods off-the-shelf.

In some sense, the first approach is the “right” one - it means that we can appropriately propagate the uncertainty in the data through to the conclusions. However, there are three main disadvantages. First, it’s typically difficult to implement this sort of averaging and often comes with a big performance hit. Second, we have to implement it separately for every method we want to run. Third, I feel that, in some sense, this kind of averaging usually includes the phasing/imputation problem, and should therefore be at least as hard. For example, a Li and Stephens model chunk-copying model that integrated over phase would naturally generate haplotype estimates as well (see here, for example). Given this, maybe we should try to use all the technology that’s already been developed for phasing and imputation, rather than reinventing it within other methods. Taking the second approach also has the advantage that we can easily and naturally incorporate information from external reference panels to improve our data.

An example

As a first pass at getting this to work, I looked at 196 UDG-treated samples from Mathieson et al. Briefly:

- For each site in the 1240K capture array, I computed genotype likelihoods, just based on the binomial likelihood of allele counts, with a small error probability.

- Then I used beagle to phase, infer missing genotypes, and impute - using the 1000 Genomes phase 3 EUR samples as a reference panel. You actually have to run beagle twice, once to phase and infer missing genotypes and then again to impute at ungenotyped sites.

I felt like since all the ancient samples have ancestry that is represented in the present-day EUR sample, it would be reasonable to use a reference panel.

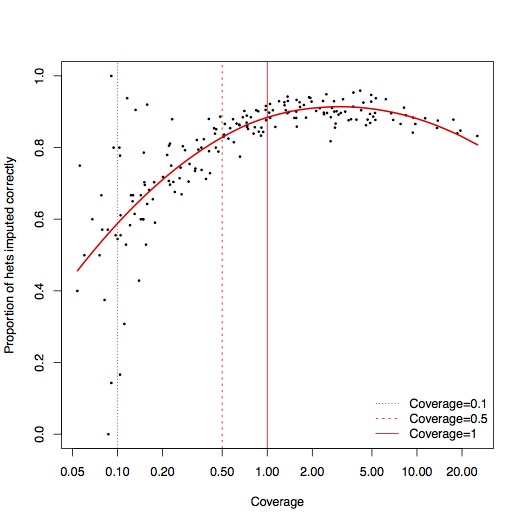

To test accuracy, for each sample, I masked out 1% of all the sites where we saw reads with both alleles. Excluding errors, these sites should be heterozygotes, so we can measure the accuracy of the imputation by seeing how many of these heterozygote sites we recover:

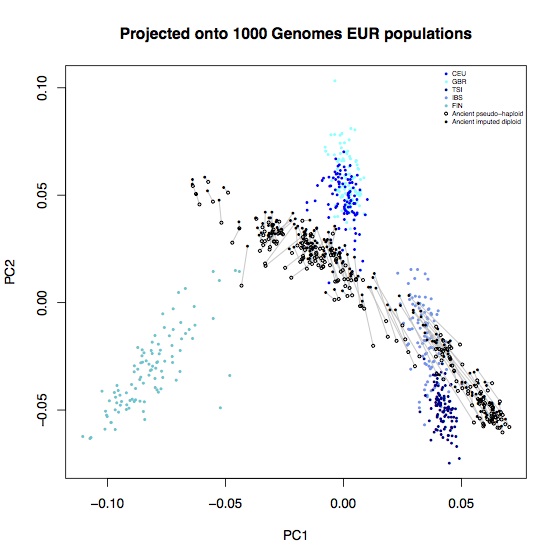

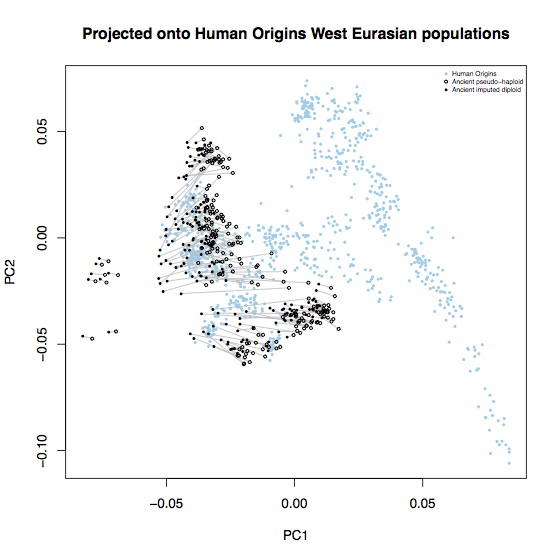

Above coverage of around 0.5x, it seems like you can reliably impute 80-90% of heterozygote sites. In the interests of completeness, I didn’t do any filtering of poorly imputed sites, so it’s likely that some of these could be removed2. A few percent of these are also likely to not actually be heterozygotes, particularly at CpG sites. To see what effect these errors had on population genetic analysis, I computed the principal components for these samples, projected onto axes defined by the 1000 Genomes EUR samples, and also onto axes defined by 777 West Eurasian samples from the Lazaridis et al. Human origins dataset. Each open circle represent an ancient sample with the original pseudo-haploid data, linked with a line to a solid circle representing the imputed diplod data for the same sample.

Most of the imputed samples are reasonably consistent with the unimputed data, but there are some systematic shifts. In particular, all samples are systematically shifted towards hunter-gatherers (the leftmost ancient samples on each plot); leading to some alarming D-statistics:

P1 P2 P3 P4 D-stat Z-score

Mbuti Loschbour.SG LBK_EN LBK_EN.imputed 0.0264 21.229

Mbuti Loschbour.SG Corded_Ware_Germany Corded_Ware_Germany.imputed 0.0336 17.331

Mbuti Loschbour.SG Anatolia_Neolithic Anatolia_Neolithic.imputed 0.0190 26.498

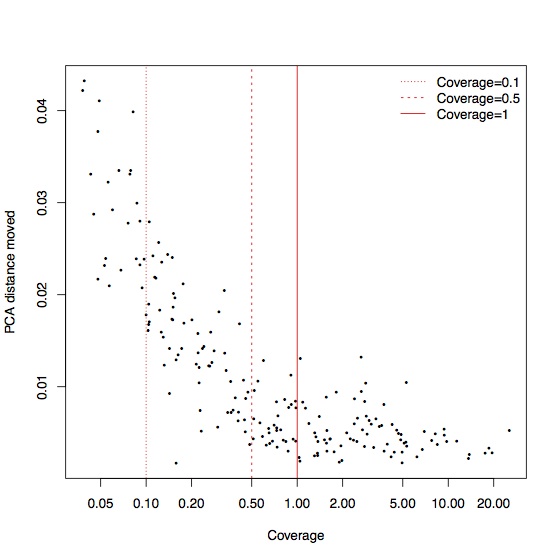

This is driven largely by a small number of samples that move a lot, but these tend to be the samples with the lowest coverage. Again, for coverage greater than 0.5x, most of the samples are relatively stable in PCA space:

The imputed data also seems attracted towards human outgroups, possibly because of a higher error rate or because imputation exacerbates the ascertainment bias of the targeted SNPs.

P1 P2 P3 P4 D-stat Z-score

Chimp Mbuti LBK_EN LBK_EN.imputed 0.0047 4.390

Chimp Mbuti Corded_Ware_Germany Corded_Ware_Germany.imputed 0.0053 3.293

Chimp Mbuti Anatolia_Neolithic Anatolia_Neolithic.imputed 0.0074 10.786

Clearly the imputed data in their current state are not suitable for population genetic analysis of this type. I did a pretty simple-minded analysis here, but even so, I think it’s likely that imputation will always introduce subtle biases into this kind of analysis so it’s going to be difficult to convince ourselves that any signals of differences between individuals or populations that we discover in imputed data are actually real. On the other hand, analyses where we can compare across the genome, within individuals, such as selection scans, would allow us to correct for inter-individual variation in imputation quality, and I think this is where this kind of approach will be really useful.

Next steps

As I mentioned above, I did a very simple-minded analysis here, and I’m sure it could be improved. In particular:

-

The genotype likelihoods could be much better calculated. In particular, the error rate is highly context-dependent (probably varying by several orders of magnitude), and properly implementing that would potentially be a big improvement.

-

I didn’t do any post-imputation filtering here, for the sake of completeness, but in principle, that could remove a lot of bad calls. It’s not immediately obvious to me what the right thing to do is, though.

-

Different, or larger, reference panels might help. I used 1000 Genomes because that’s what I had immediately available and it made the imputation relatively fast, but I imagine something like the HRC would improve things a lot.

-

In phasing diverse present-day samples, I’ve found that using phase-informative reads helps a lot. I’m not sure it would be so useful here, because the fragments are typically very short, but it might be worth a try.

-

I’ve focused on capture data here, because that’s what I have most of, but I’m also interested in applying the same sort of approach to shotgun data. It’s a slightly different problem, but there’s a careful analysis in Gamba et al., and it seems promising.

Finally, there’s not much published work in this area, and it would be very helpful to figure out what the best practice is, so if you’ve worked on imputing this dataset, or some other ancient DNA dataset, and you’d like to compare results, or discuss anything about the analysis, please get in touch!