Two papers came out recently about spatially explicit models for genetic data (SpaceMix, by Bradburd et al., and EEMS, by Petkova et al.). As far as I can tell, work in this area is largely driven by ecology, and it hasn’t really taken off in human genetics. I’m not sure there’s a good reason why not, so I tried them out on a well-studied human dataset to see what they came up with. The two methods basically fit the same model, in which the genetic correlation between populations is proportional to some scaled distance measure, but they differ quite a lot in the visualisation. EEMS was a bit of a pain to install, but apart from that, they are both easy to run and extremely well documented. Both sets of authors obviously put a lot of effort into the code, which is well-structured and commented, and could easily be further developed by others. I’d say two great examples of how methods papers should be done.

Data

I used the Human Origins dataset from Lazaridis et al. (2014), available here. After some experimentation, I restricted to 827 samples, roughly in the box from 5’E-54’W longitude and 27’N-71’N latitude, which covers Europe, some of the Middle East, and some of North Africa. I also excluded the Kalmyks. I thought this should contain a nice mix of isolation-by-distance (IBD), as well as a history of major migrations and some major geographic barriers.

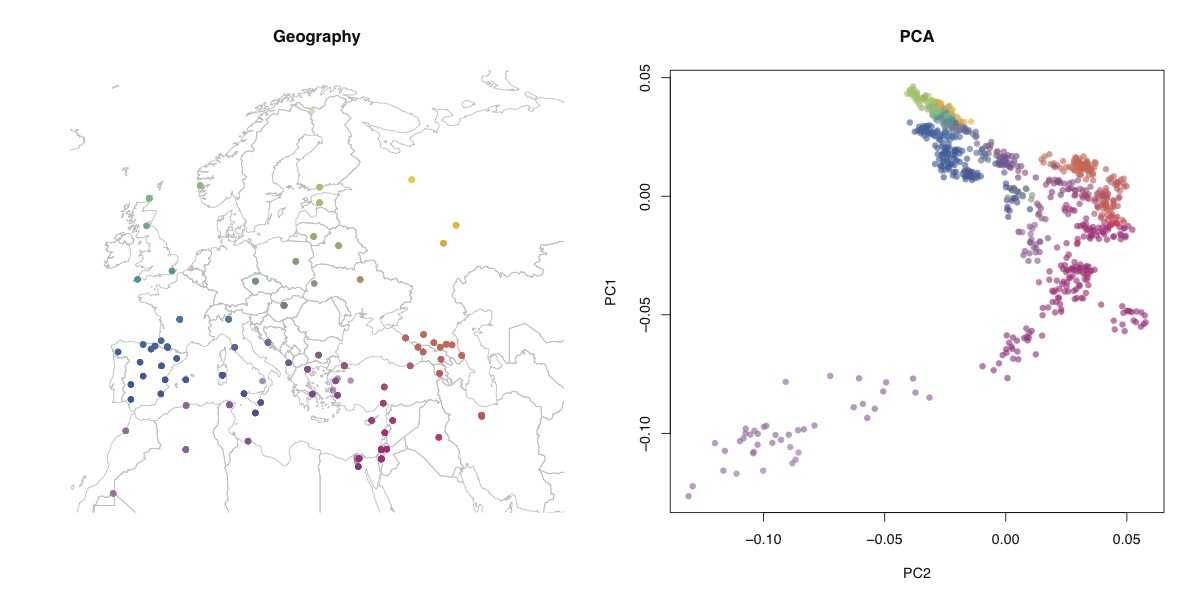

Above, you can see the geographic locations of the samples, as well as the first two principal components. Basically, the North-West African samples are very differentiated by the PCA, and the rest of the samples look, at least qualitatively, like a map of Europe, as expected.

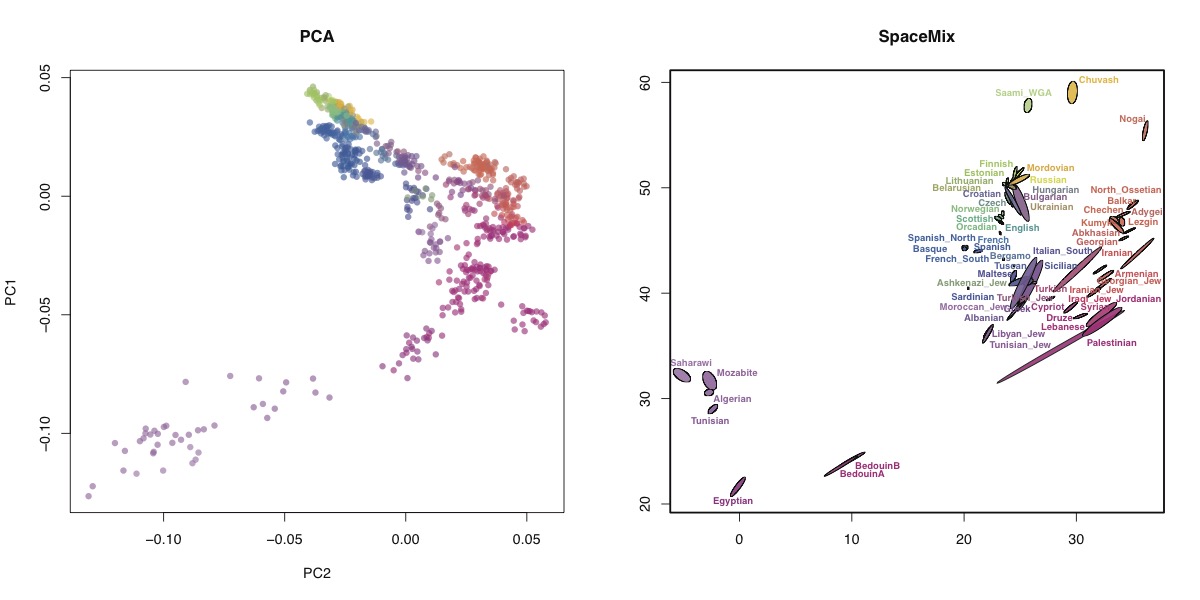

###SpaceMix I ran SpaceMix with and without spatial priors (i.e. using the true locations of the samples as priors for the geogenetic distance), and it didn’t seem to make much difference. Here’s the result of the SpaceMix analysis, compared with PCA (95% credible ellipses). Basically what SpaceMix is doing is finding positions for populations in some theoretical “geogenetic” space, such that the genetic correlation between populations is proportional to the geogenetic distance.

Note that the SpaceMix analysis included a Procrustes transformation to get as close as possible to the geographic co-ordinates, which I didn’t do for the PCA. I included admixture edges, but there didn’t seem to be any very strong admixture events, which suggests, I suppose, that the data is fairly consistent with IBD. The main admixture inferred is into Palestinians, Jordanians and Egyptians, from somewhere up in the top-left corner, which I’m not really sure how to interpret. Overall, the SpaceMix analysis seems fairly consistent with the PCA. Some populations, like the Saami, are more clearly differentiated by SpaceMix, but that might be because I ran the SpaceMix analysis on populations rather than individuals (mostly for computational reasons). I like this visualisation because it’s very intuitive and has a simple interpretation. In this case you don’t learn much that you didn’t get from PCA, but I guess that’s because these data are fairly consistent with IBD and the real power of SpaceMix is to learn about admixture.

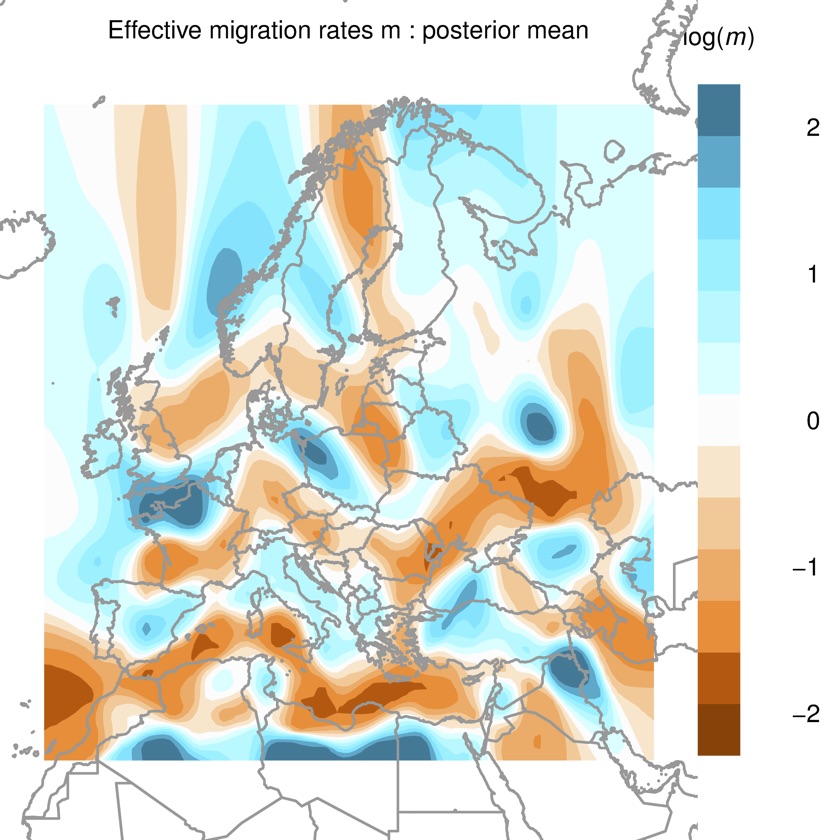

###EEMS EEMS takes a different approach to visualisation - rather than placing populations in a theoretical space, it fits a migration rate surface in real geographic space. This means that you can stare at the output and try and match up migration barriers with geographic features. Here’s the output:

This is a beautiful visualisation. It looks like the Mediterranean is a major barrier to migration, as are the Alps and maybe the Carpathians, and there are high migration routes along both the north and south coasts of mainland Europe, as well as Northern Britain to Scandinavia, and Anatolia to the Middle East. Sounds plausible. Some of the other features are not so clear, for example, the barrier in Northern Sweden, which is probably just there to separate the Saami from other Scandinavians.

###Time One thing that I’m struggling with is how to reconcile the results from these models with what’s known about the migration histories of this region. For example, EEMS infers a migration barrier between Anatolia and Europe, even though we know that a significant proportion of the ancestry of present-day European derives from Anatolia. I guess that’s because present-day Anatolians are not very closely related to Neolithic Anatolians, so you can’t really blame the method, but it is a bit confusing. Similarly, I interpreted the SpaceMix results as being broadly consistent with IBD, even though we know that hasn’t always been true. I can think of a couple of reasons why that might be true.

- Maybe the major migrations of the past ten thousand years didn’t actually disturb the spatial structure that much. They’re very obvious, because the migrating populations are so different from each other, but overall IBD still dominates patterns of genetic variation.

- Conversely, perhaps the migrations are largely correlated with the spatial structure that derives from IBD, or just average out over time to the same thing.

One thing that might help to resolve this would be adding a temporal aspect to these methods. As it is, there’s some implicit time-averaging in the construction of the covariance matrix (depending on the frequency of the SNPs and how much you LD prune). In principle though, you could separate out the different time-slices. How cool would it be to see the effective migration surface changing over time, with corridors opening and closing corresponding to specific migrations? I think this would probably not be possible to do using present-day data alone, and the sampling of ancient data is still too spotty, but I think it will soon be more feasible. It sounds like the SpaceMix authors are working in this area, and I look forward to seeing what they come up with. Another idea might be to use only rare variants, or use the identity-by-descent matrix instead of the allelic covariance matrix, both of which would focus only on much more recent history.